Why Deterministic Browser Automation Beats AI Agents

Chris Schlaepfer|CEO & Co-founder

In our welcome post, I mentioned that we've developed some opinions about the current AI landscape, particularly around automation. I figured it'd make sense to kick off this blog with a discussion on perhaps the most important of those opinions, which has shaped the entire direction of our company: why we chose deterministic browser automation instead of building around AI browser agents.

It's not particularly clear where we are in the AI hype cycle, but in the current moment, not leaning 100% into AI doesn't feel like an obvious choice. When we started Chorrie (our pre-pivot healthcare automation company), we were genuinely excited about browser agents and their potential to automate away busywork. Projects like:

promise a world where you can point an AI at a browser, describe a workflow in natural language, and watch it navigate a complex UI. It felt like the future.

But over time, the gap between the promise of agents and the reality of using them in production workflows became impossible to ignore.

The Appeal of Agents (and Why We Wanted Them to Work)

On paper, agents seem like the perfect abstraction. In contrast to Selenium or Playwright scripting, they promise the flexibility of a human operator without the tedium of maintaining brittle selectors and test breakages. They suggest a world where automation is as simple as describing the task, and the model handles everything.

To their credit, for relatively simple, linear tasks, that story actually holds up quite well. But the moment you ask agents to perform tasks with real-world complexity, the wheels start to come off.

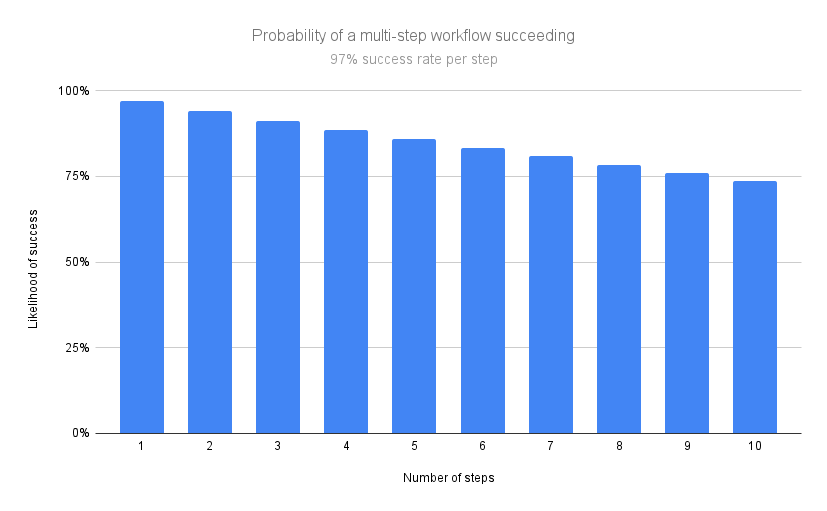

Because agents are non-deterministic, we can't guarantee what they will do at each step as they complete a task - so each step has an associated success probability. This means that, as the number of steps it takes to complete a task increases, so too does the failure rate.

Consider an agent with an average 97% per-step success rate. When it performs a task with just 10-steps, suddenly our success rate drops from 97% to 75%.

This is hardly acceptable for a production workflow, especially in industries where you're dealing with sensitive data. We saw this firsthand when automating medical coding tasks - the more encounters we had to process, the higher the likelihood the automation went off the rails.

Where Agents Broke Down for Us

Unpredictable Drift

See above - the issue we most consistently ran into was drift. And it wasn't for lack of trying - we spent weeks carefully crafting prompts, structuring tool instructions, and adding a lot of guardrails. Still, agents would periodically deviate from the expected workflow.

My favorite failure we encountered was when we built a browser agent to process simple medical claims in our client's EMR. We provided it with a regular expression that identified the right claims, and a custom tool which it could pass the regular expression to in order to reliably get those claims. During one run, the filter didn't match any items - which meant the agent should be done (a condition which we explicitly outlined in our agent's prompt).

Our agent didn't like that it got no results, so it decided to retry after "relaxing the regex restrictions" to see if it could find some claims to submit!

This was an entirely new failure in a case that had succeeded several times before. We had no concept of this happening because it had done it right so many times before - and so finding the source of the issue was extremely challenging. Which leads us to…

Difficult, Ambiguous Debugging

Debugging scripts is straightforward, if a bit annoying. When code breaks, you can inspect the error, isolate the issue, find the offending code, and fix it. When agents fail, we're left deep diving into ambiguous logs, diffing prompts, speculating about model behavior, and hoping the next run behaves differently.

Debugging became less about engineering and more about managing uncertainty. Often our approach to this was scripting individual steps in the workflow and having our agent invoke them as tool calls.

By the time we got the workflow to a place where it was truly reliable, we stepped back and looked at what we made: a Frankenstein's monster of scripts, held together by a GPT-powered central nervous system. It never asked to be created. We're sorry we ever did.

Unsustainable Cost Structure

Ok, but let's assume that agents become perfect, able to navigate complexity and ambiguity with 100% per-step reliability. Even with these assumptions, we hit a wall on cost.

Subject-matter experts are good at real-world workflows because they have the context needed to perform their tasks; they're trained professionals, and have acquired that context over years of experience. I couldn't begin to tell you how many obscure and idiosyncratic edge cases the medical billing teams we worked with had innately memorized.

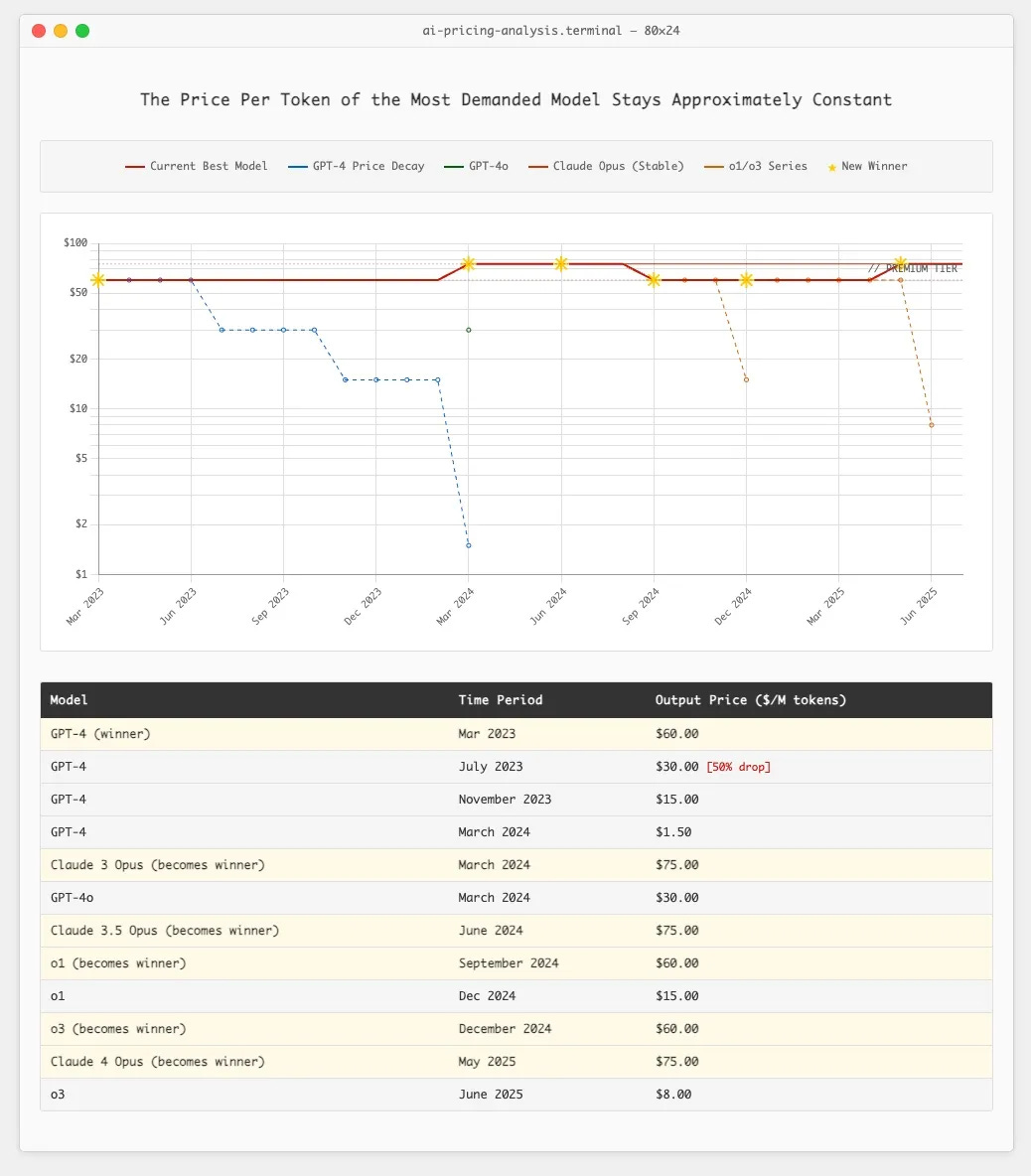

All that context needs to be fed to the agent for successful execution, and as workflows got more complex, we started absolutely burning through tokens. And unfortunately, we simply can't rely on models getting cheaper. I won't go into it here, but Ethan Ding wrote an excellent article this summer on the fallacy of relying on token costs going down - I've included a relevant screenshot below.

Latency That Doesn't Scale

Perhaps not the biggest concern for us, but worth mentioning, was latency. Each browser action triggered another model call, which could add up to 10s of seconds per call, quickly compounding to minutes for even straightforward workflows.

Even straightforward tasks began to feel slow, and while we weren't in a huge time crunch for the execution of our healthcare operations use case, it became an issue with debugging. Every time we needed to tweak our automation, be it a script or a prompt update, we needed to re-run the whole thing from scratch. "Watching paint dry" doesn't quite cover the tedium of making updates to these workflows.

Why Deterministic Scripts Still Win in Production

Back to Frankenstein - despite the monster we had created, we looked at what was working well. And wouldn't you know it, the most reliable part of the whole system was the deterministic scripts the agent was using as tool calls to execute actions.

These scripts (written in Playwright) had a tendency to grow in scope as they took on more and more "responsibility", and were consistent, testable, debuggable, and predictable. If something broke, we knew why. If the UI changed, we pasted the DOM into Claude Code and told it to fix the issue. And we weren't setting tokens on fire in the process.

Reliability, execution cost, maintenance cost - as systems scale, these qualities have a huge impact on the customer's bottom line as well as our own. To illustrate the point: the first agent-based automation we wrote would have cost us about $4k a year to run in token costs alone. Including all hosting and other variable costs, the script we wrote to replace it will cost less than $200.

That said, deterministic automation isn't perfect. Writing Playwright scripts is slow. Maintaining selectors is annoying. Debugging is tedious. That's one of the reasons agents became attractive in the first place: better ergonomics.

So instead of replacing scripts with agents, we asked a more practical question:

What if we kept the reliability of scripts, but dramatically improved the workflow around building and maintaining them?

That became the seed for BrowserBook.

Why We Built BrowserBook the Way We Did

When we made the pivot, our goal wasn't to reject AI, it was to use it more responsibly. We wanted a system where AI accelerates development rather than driving execution. We wanted something we, as engineers, would actually use, and that we wished we had during our healthcare automation days.

That led us to a few core decisions:

- Use Playwright, not AI, as the execution engine.

- Wrap it in a notebook-style IDE with individual cells so you can debug workflows incrementally.

- Embed an inline browser so we don't have to context switch during development.

- Use AI where it shines to generate code, automatically providing the necessary browser context.

- Build features for the things that slowed us down: managed auth, screenshot utilities, data extraction, etc. - so developers don't waste time reinventing infrastructure.

In other words: keep the reliability of scripts, make the development experience feel as smooth as possible, and let AI serve as an assistant rather than an unpredictable agent.

That philosophy will guide us into future features too - including the self-healing work we've hinted at. But even there, our approach is grounded: self-healing needs deterministic anchors. You can't "heal" chaos; you can only heal structured, traceable workflows.

Closing Thoughts

When we first started exploring automation tools, we wanted to believe that browser agents were the future, but when you spend enough time building high-stakes automations, you develop a deeper appreciation for predictability. I can't tell you how many times Jorrie and I stayed up into the wee hours babysitting our browser agent as we prayed it didn't do something ridiculous.

Agents are exciting, and they'll continue to have a role, especially in prototyping and simple workflows. But when reliability matters, determinism still wins. That's the foundation we chose to build on, and so far, it's been the right call for us and for our early users.

As always, we're open to being wrong. If you've had great success running browser agents in production, we'd genuinely love to hear about it. The community is evolving quickly, and these discussions help us all get better.

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for more on BrowserBook. If you want to stay updated, you can follow us on LinkedIn, X, or join our Discord server.